Residence

In Jeanne d'Arc's time: Rare expo on the arts in France in the time of Charles VII (1422-1461)

A retelling of the Brothers Grimm’s The Robber Bridegroom from the point of view of the old woman in the cellar, featured in Our Lives Are Fairy Tales. Read on for some background info that led to this retelling.

Writing The Robber Bridegroom’s Wife

Some of my earliest memories of German children and fairy tales go back to our family visits to Saarbrücken in the early 90s. Our grandmother’s house was full of children’s books in German, which as a French-speaking Molenbeekienne Brussels resident, I couldn’t read or understand. But their cute and colorful illustrations stood out enough to draw my attention and curiosity.

Fast forward to a move to the US and becoming bilingual. To my somewhat pleasant shock, I noticed the closer linguistic similarities and felt it was easier to learn (at least some?!) German after knowing English rather than French. I took one year of German in high school and would’ve loved to continue it, but it wasn’t meant to be.

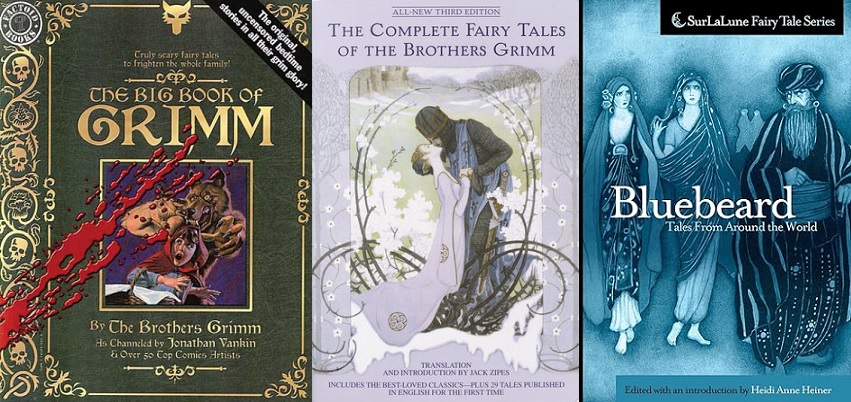

My middle school interest in fairy tales had me immersed in an eclectic mix, at which point I ran into Bluebeard and its variant, The Robber Bridegroom. This lingering interest in RB followed me into high school, when I discovered the illustrated Big Book of Grimm (reminding me of Belgian comics), and I even wrote an RB version as a woman villain for an English class assignment. (*I note that it wasn’t until years later that I heard of the potential connection between Bluebeard and Gilles de Rais, former partner-in-arms to Jeanne d’Arc. At this point I’m not very convinced by this connection but either way, the stories are very different.)

Once again, this interest morphed when I revisited the tale years later and wondered about the old woman in the cellar. Who was she and where did she come from? She’s only seen at the end and is not mentioned besides that, so the creative urge seized me to explore that point of view through a short story.

On the writing front, The Robber Bridegroom’s Wife was one of those early short stories that just flew out of me. Writers know that it’s not always the case and can even feel rare, so creating this story was a pleasant–and in many ways ‘ideal’–writing experience. But it bears repeating that this ‘ease’ should not be the reference point, otherwise there wouldn’t be much writing getting done at all, ever. 🙂

What I love about reading–and how I initially prefer to experience stories–is to see how they are told and the overall initial impact on me. This is often surprising and not always obvious. It’s also fascinating to dig further on history, symbolism and the like, but I think there can be such a thing as ‘overexplaining,’ too. As to what the old woman might symbolize, there’s surely different interpretations, but I assume that she could represent a woman’s intuition.

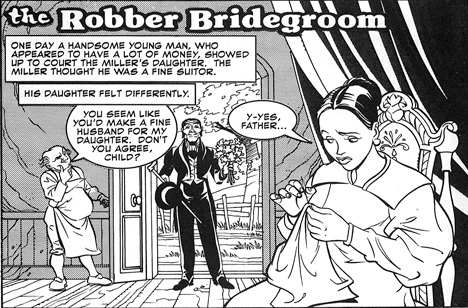

Given her brief presence in the written tale, it might not be surprising that the old woman is hardly seen in illustrations. So it might be fair to say that the below is possibly the only illustration of her, to my knowledge.

For a book on uncensored fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm, Jack Zipes’s Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm is a great one. (Fittingly, I have a small book on French fairy tales that uses the same image for its cover–and can serve as a fitting reminder of the way folk and fairy tales move across neighboring landscapes and cultures.)

One source who has compiled global stories of the Bluebeard theme is Heidi Anne Heiner, also known as Sur La Lune fairy tales in her bulky Bluebeard volume. I love the concept of gathering them all in one place that can be useful for reference and research. The SurLaLune series also offers other collections of popular fairy tales by subject matter, like Beauty & The Beast, The Little Mermaid, Cinderella, etc.

One modern take on the Bluebeard theme that I also love is Belgian author Amélie Nothomb’s ‘Barbe bleue’ (Bluebeard). Since French titles are not always easy to find in the US, I’d spontaneously borrowed it from UC Berkeley’s library stack while tracking down titles for research on my 6th century novel, Jayida.

I’m so glad that out of her dozens of books, I chose to begin with that one. This novella written mostly in dialogue reveals the two main characters of Saturnine and the older nobleman Don Elmirio, often with a biting sense of humor. It was the kind of story that packed so much I loved into a concise space, so that if I don’t enjoy anything else of hers as much, it was enough to make its positive mark on me. Unfortunately I don’t think it’s translated to English, but hopefully that will change in due time. I’ll close with some favorite quotes translated below to give an idea of this gem:

-Je vois que vous êtes un esprit fort. Ce n’est pas votre faute. Vous êtes française.

-Non. Je suis belge.

(I see that you have a strong spirit. It’s not your fault. You’re French.

No, I’m Belgian.)

Quand on tombe amoureux, on négocie après coup avec soi-même, histoire de voir si on s’autorise cette absurdité.

(When we fall in love, we negotiate with ourselves afterwards, to see if we allow ourselves this absurdity.)

Je ne suis pas un fou, mais un homme épris d’absolu, confronté par neuf fois à une question terrible: quelle est la juste frontière entre l’aimée et soi?

(I’m not a madman, but an infatuated man, confronted nine times with a terrible question: what is the proper limit between the beloved and oneself?)

Read The Robber Bridegroom’s Wife in Our Lives Are Fairy Tales.